Farewell Professor

Afterimage

(from the RUSH album Grace Under Pressure, 1984)

lyrics by Neil Peart

Suddenly —

You were gone

From all the lives

You left your mark upon

I remember —

How we talked and drank

Into the misty dawn

— I hear the voices

We ran by the water

On the wet summer lawn

— I see the foot prints

I remember —

— I feel the way you would

— I feel the way you would

Tried to believe

But you know it’s no good

This is something

That just can’t be understood

I remember —

The shouts of joy

Skiing fast through the woods

— I hear the echoes

I learned your love for life

I feel the way that you would

— I feel your presence

I remember —

I feel the way you would

This just can’t be understood…

********

These lyrics are fitting, as Neil wrote them in remembrance of Robbie Whelan, a friend who died in a car crash at the age of 31. Robblie was an engineer at Le Studio in Quebec and worked on several of Rush's albums, most notably Moving Pictures and Signals.

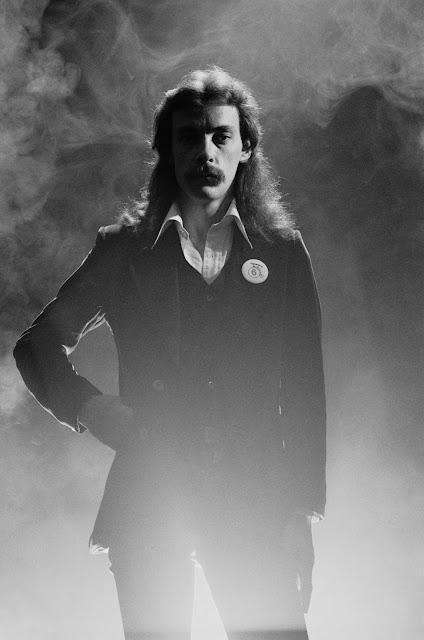

Who Is That Drummer?

I first came across Neil Peart back in, I think, 1975. RUSH was the opening band on a 3-band bill. I remember thinking that the band was OK, but if they didn’t make it, I was sure the drummer would, because he was really great and stood out. I found out who the band was and bought their latest LP, Caress of Steel. I also found out that the drummer wrote the lyrics. I was even more impressed. Then 2112 came out and as they say, the rest is history.

Back then I was playing in a power trio that played hard rock covers and our own sci-fi influenced prog. To say Neil had an influence on me would be an understatement. Neil (along with Bill Bruford of King Crimson and Alan White of YES), inspired me to expand my drum set with gongs, bells, timpani and other percussion. Instead of just playing beats, I devised complex arrangements for our songs where I orchestrated everything I played. Over the years I also played a lot of RUSH songs, and it was always a challenge to play them with the same drive and precision that Neil did.

Consequently, I also wrote lyrics for a lot of the the bands I was in at the time. I was, and still am, a voracious reader and wrote about subjects that crossed my mind. So Neil and I had that in common too. I went on to write for magazines and publish various books. To top it all off, I'm also an introvert who would rather read a good book than go out and party after a gig. So all these years I really identified with, and understood much of Neil and his life. And being 3 years younger than him, he was a role model for what I aspired to do with my life, both musically and as a writer. That's why his passing has really hit me. It's hard to believe he's gone.

A Concert Closeup

Another story: the record store I worked at back in the mid-1970s was a co-sponsor of a RUSH concert. The band had just started touring the A Farewell to Kings LP (which I don't even think was released yet) and were headlining in a small movie theater (maybe 1,500 seats, with Anthem label mates Max Webster opening the show). Some of us were in the theater early to help out with things. I remember I got to deliver donuts to the band in their grey RV they traveled in. This was before they moved up to large tour buses.

I also ended up on stage and was yelled at for walking on the white carpet they had, because they wanted to keep it clean. The drums were all covered up and we couldn't see them (Now this was in the pre-internet days, so even though Neil had been using his new drum set up for a few months, unless you had seen one of their concerts, you didn't know it).

Max Webster's set was great and the band was really impressive. We had been playing their debut album, Hangover, in the store for a few weeks, so we were well versed on their music. As great as they were, we were not at all prepared for RUSH. When the band was ready to start, they uncovered the drums and Neil had that brand new black chrome Slingerland kit with all the percussion around it. It was huge! 2 bass drums, snare, 8 toms, and all sorts of percussion hanging from a rack around his kit. My friends and I looked at each other in amazement. As a drummer, I was in awe. The concert hadn't even started and we were blown away! Finally the band took the stage. All 3 were wearing some sort of silk kimono. They certainly looked like rock stars. When the band launched into new songs like Xanadu, we were speechless. What an amazing show!

Writer Interviews Writer

Fast forward to 1988, when I was writing a lot of articles for various music magazines. I was scheduled to interview Neil after a concert. The show ended and I was ushered backstage. This was the last date of the 1st leg of a lengthy tour (maybe the Hold Your Fire tour). The band was in one of the dressing rooms having some sort of heated discussion. I sat there for quite a while, listening to the muffled voices, while the crew packed and loaded the band's gear. Finally, Neil came out and apologized for the wait and said we’d have to do the interview some other time. I later heard rumors that the band was on the verge of splitting up that night.

Fast forward a while more and I got a call from Neil to do the interview over the phone. He was very cordial and in a great mood. We had a great talk and he really opened up about their music.

My idea was to take a chronological look at all of RUSH's albums up until that point in time (Fly By Night through A Show Of Hands), and how Neil viewed them in retrospect. Conducted in April of 1989, Neil was very open and candid about RUSH's evolution as a band and as song writers.

This interview was intended for a drum magazine that folded before it could be published. I then split it into 2 parts and published it in the summer and fall issues of Drum Science, a zine I put out in the early 1990's. I did have Part 1 up on my old website for many years, but I couldn't find a copy of part 2. Unfortunately, everything was stored on old floppy discs, which I had no way to access. Finally, while searching through a lot of files a few weeks ago, I found a printed copy of Drum Science with Part 2. I put together both parts and edited it into the form you will find here. This is the 1st time in nearly 30 years that the complete interview has been available.

“The whole science of arrangement has become, through that period, the focus. At that time the focus was learning and playing the instruments—everything was instrumental. That's what mattered, the little pieces of music. After we went through that, the focus shifted, right up to the present day, the focus is on arrangement—how to put the pieces of music together. That was an important learning process that established something and allowed us to put something to sleep too. Many musicians never get out of the trap of technique being the end of everything. It's still very important, but I'll never be one of the less is more minimalists. I'm never, ever going to say that feel is more important than technique. There's no comparison, unless you know how to express it, it doesn't matter how much you can feel it. That's also an important distinction we had to learn. At the time we didn't know it. Technique was more important than anything else. But that's okay, I think it served its purpose. At a point in anyone's development in a craft or job, you have to go through a period in which the nuts and bolts of the job are absolutely what matters most.”

Whether you liked Neil’s drumming, or RUSH, doesn’t really matter. But every drummer owes him a great debt for making the drums and drummer so visible to the public. And also for inspiring so many people to take up the drums and strive to move drumming forward. He was a quiet man with a big heart, and even bigger drumming. Thanks for the memories Neil!

~ MB

(from the RUSH album Grace Under Pressure, 1984)

lyrics by Neil Peart

Suddenly —

You were gone

From all the lives

You left your mark upon

I remember —

How we talked and drank

Into the misty dawn

— I hear the voices

We ran by the water

On the wet summer lawn

— I see the foot prints

I remember —

— I feel the way you would

— I feel the way you would

Tried to believe

But you know it’s no good

This is something

That just can’t be understood

I remember —

The shouts of joy

Skiing fast through the woods

— I hear the echoes

I learned your love for life

I feel the way that you would

— I feel your presence

I remember —

I feel the way you would

This just can’t be understood…

********

These lyrics are fitting, as Neil wrote them in remembrance of Robbie Whelan, a friend who died in a car crash at the age of 31. Robblie was an engineer at Le Studio in Quebec and worked on several of Rush's albums, most notably Moving Pictures and Signals.

Who Is That Drummer?

I first came across Neil Peart back in, I think, 1975. RUSH was the opening band on a 3-band bill. I remember thinking that the band was OK, but if they didn’t make it, I was sure the drummer would, because he was really great and stood out. I found out who the band was and bought their latest LP, Caress of Steel. I also found out that the drummer wrote the lyrics. I was even more impressed. Then 2112 came out and as they say, the rest is history.

Back then I was playing in a power trio that played hard rock covers and our own sci-fi influenced prog. To say Neil had an influence on me would be an understatement. Neil (along with Bill Bruford of King Crimson and Alan White of YES), inspired me to expand my drum set with gongs, bells, timpani and other percussion. Instead of just playing beats, I devised complex arrangements for our songs where I orchestrated everything I played. Over the years I also played a lot of RUSH songs, and it was always a challenge to play them with the same drive and precision that Neil did.

Consequently, I also wrote lyrics for a lot of the the bands I was in at the time. I was, and still am, a voracious reader and wrote about subjects that crossed my mind. So Neil and I had that in common too. I went on to write for magazines and publish various books. To top it all off, I'm also an introvert who would rather read a good book than go out and party after a gig. So all these years I really identified with, and understood much of Neil and his life. And being 3 years younger than him, he was a role model for what I aspired to do with my life, both musically and as a writer. That's why his passing has really hit me. It's hard to believe he's gone.

A Concert Closeup

Another story: the record store I worked at back in the mid-1970s was a co-sponsor of a RUSH concert. The band had just started touring the A Farewell to Kings LP (which I don't even think was released yet) and were headlining in a small movie theater (maybe 1,500 seats, with Anthem label mates Max Webster opening the show). Some of us were in the theater early to help out with things. I remember I got to deliver donuts to the band in their grey RV they traveled in. This was before they moved up to large tour buses.

I also ended up on stage and was yelled at for walking on the white carpet they had, because they wanted to keep it clean. The drums were all covered up and we couldn't see them (Now this was in the pre-internet days, so even though Neil had been using his new drum set up for a few months, unless you had seen one of their concerts, you didn't know it).

Max Webster's set was great and the band was really impressive. We had been playing their debut album, Hangover, in the store for a few weeks, so we were well versed on their music. As great as they were, we were not at all prepared for RUSH. When the band was ready to start, they uncovered the drums and Neil had that brand new black chrome Slingerland kit with all the percussion around it. It was huge! 2 bass drums, snare, 8 toms, and all sorts of percussion hanging from a rack around his kit. My friends and I looked at each other in amazement. As a drummer, I was in awe. The concert hadn't even started and we were blown away! Finally the band took the stage. All 3 were wearing some sort of silk kimono. They certainly looked like rock stars. When the band launched into new songs like Xanadu, we were speechless. What an amazing show!

Writer Interviews Writer

Fast forward to 1988, when I was writing a lot of articles for various music magazines. I was scheduled to interview Neil after a concert. The show ended and I was ushered backstage. This was the last date of the 1st leg of a lengthy tour (maybe the Hold Your Fire tour). The band was in one of the dressing rooms having some sort of heated discussion. I sat there for quite a while, listening to the muffled voices, while the crew packed and loaded the band's gear. Finally, Neil came out and apologized for the wait and said we’d have to do the interview some other time. I later heard rumors that the band was on the verge of splitting up that night.

Fast forward a while more and I got a call from Neil to do the interview over the phone. He was very cordial and in a great mood. We had a great talk and he really opened up about their music.

My idea was to take a chronological look at all of RUSH's albums up until that point in time (Fly By Night through A Show Of Hands), and how Neil viewed them in retrospect. Conducted in April of 1989, Neil was very open and candid about RUSH's evolution as a band and as song writers.

This interview was intended for a drum magazine that folded before it could be published. I then split it into 2 parts and published it in the summer and fall issues of Drum Science, a zine I put out in the early 1990's. I did have Part 1 up on my old website for many years, but I couldn't find a copy of part 2. Unfortunately, everything was stored on old floppy discs, which I had no way to access. Finally, while searching through a lot of files a few weeks ago, I found a printed copy of Drum Science with Part 2. I put together both parts and edited it into the form you will find here. This is the 1st time in nearly 30 years that the complete interview has been available.

The one word that best describes Neil Peart is phenomenon. Whether you love his drumming or hate it (there are very vocal groups on both sides), you have to admit that he has had a major impact on rock drumming, and drumming in general. A true testament to his popularity comes from attending various drum clinics were one question is always asked of the clinician: “What do you think of Neil Peart?” Throughout the eighties, Neil won more MODERN DRUMMER magazine polls than anyone else. His response has been one of amazement and mystery. He just does his best and doesn't really know why he should be so popular.

I'll never forget the first time I saw Neil. Rush was just an unknown opening band added to a three-band billing. As such, I didn't pay much attention to them at first. The band was okay, but the drummer was something special! Seated behind a chrome Slingerland double bass kit, he played with such precision and authority. I wasn't sure if the band would ever be a hit, but I knew the drummer was destined for bigger things. The next day was spent finding out who the band, and especially the drummer was .

As it is, it's nearly twenty years later and Neil Peart and his band mates in Rush, guitarist Alex Lifeson and Bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee, are still going strong. The band is an amazing success story. With little radio airplay or record company support, they have survived the critic's scorn to become one of the most successful bands of the last twenty years.

All this has not been easy. Rush has shunned the typical rock star lifestyle and mentality, preferring instead to work hard at their music and lead an almost reclusive existence. The fact is, all three members are very private people. They have never been media darlings making the tabloid headlines. Also, with the exception of two recordings, they have not worked outside of Rush (Neil shared the drumming with Steve Smith on one track of Jeff Berlin's VOX HUMANA album, and the entire band played on the track, Battlescar from Max Webster's UNIVERSAL JUVENILES album). All this, along with their serious attitude, has helped them earn a reputation as being aloof. Far from it, they just value their privacy and want to lead normal lives.

I found Neil to be a very warm and open person. Although he doesn't believe in looking back, he was very open and candid about Rush's growth and explorations through the years. Rather than being an interview about drums and hardware, it turned into a much more interesting look at the man behind the drums

Peart joined Rush on the heels of their first album release, simply titled RUSH. At the time, the band was highly derivative of Led Zeppelin and other current heavy rock bands. When the original drummer, John Rutsey, left on the eve of their first American tour, Peart was brought in with two days to learn the material and hit the road.

Peart's first recording with the band showed a more focused group, with more depth and originality. “I think Alex and Geddy wanted to go in a different direction [than the first record],” Neil says, “but were held back by my predecessor. My enthusiasm was a catalyst, allowing them to go in a direction they wanted to.” Part of this change came from Peart's contribution as lyricist for the group. “It was an added part of the vehicle. The lyrics were more by default than anything. The other guys weren't particularly interested in doing it. I had only written two or three songs before that. I'd always loved words and reading, so I thought this was an opportunity I'd like to try. At the time, I wasn't serious about it as an ambition or a drive, but it was something that might be mildly entertaining. Gradually I did become obsessed and it became a long term goal to improve and refine it.”

Songs like Bytor And The Snow Dog expanded the music into stories of epic proportions. “I use the word vehicle, because all it is lyrically is an excuse to do a lot of things instrumentally. It's good, and the lyrics didn't mean anything really, just the simplest of fantasy stories. But what's important musically is being allowed to work in a cinematic format. That was an important step, because it carried us even up to right now. But nine or ten years ago, when we were doing a lot of involved instrumental pieces that were very cinematic in nature, that was a large step we didn't really appreciate.”

Peart's expanded lyrical ideas brought more drama to the music. “Musically, it just allows you so much scope and visualizing, that you can try to exercise your musical abilities. It was a very important writing tool, and educational too. Much of that stuff I will belittle now as being simple fantasy in the lyrical sense, and pretty formless in the musical sense, but it was school for us. Our earlier records were entirely high school, college, and then university. Step by step we we're learning how to create moods and join pieces of music together to make people feel something, without resorting to clichés or writing love songs to make people sad, or dance songs to make them move. We were trying to find something a little more legitimate.”

Rush's next release featured the side long epic, The Fountain Of Lamneth. They were expanding into the more progressive territory dominated by English bands like YES, ELP, and King Crimson. “It was a continued evolution, but dealing with more serious themes musically and lyrically. Again, it was like the second year of high school—that's the best analogy I can make. We were learning more and trying to apply it, being swept away by ourselves.

“In realistic terms, it sold exactly the same [as FLY BY NIGHT], which is a circumstance record people find hard to deal with. Ironically, FLY BY NIGHT was always perceived as being very successful, with CARESS OF STEEL being less so. But what FLY BY NIGHT had been, was promising. It sold 125,000 copies, hardly earth shattering, but it was promising and still would be for any band today. The problem on the business side was that CARESS OF STEEL did not live up to it [by selling more]. But this was an album that we loved making and we were very proud of it when it was done. We learned a lot and to my mind it still shines brightly.”

In the wake of CARESS OF STEEL, the record company looked at the short term bottom line: sales figures. “They're supposed to look at the numbers. I have no problem with that, but I have a problem with narrow vision and shortsightedness. That's the side of business I object to. I'm not anti-business, I recognize the reality of someone doing that side of things. But I don't want to be a salesman, or manufacture and promote our records ever. That's not my ambition in life. There is a part where all artists need the business side to look after their affairs and help expose them to a potential audience. But I have a problem when they won't.”

Record companies are always looking for a new band that can have a million selling debut recording, but these instances are rare at best. “It took us four albums, right up to 2112, to break even and pay for ourselves. Up to that point they were writing us off. The year we released 2112, they had written us off and we were going to be totally negligible in their future. As it happened, that album went gold and established us with power and independence of our own. But even after succeeding without hit singles, by hard work and sincere music with integrity, they would not take that as a valid example. That's ridiculous, because to them it has to happen instantly, or why should they invest their time and money without knowing that the return is going to be quick. That to me is just bad business. In the last 19 years we've seen so many bands come up and be the big thing for six months. We would be ignored by the record company, then they would die out and we would be stars again. In their estimation we go up and down, but in reality we just keep going along selling a good number of records. We're consistent and do well on each of our tours, but it's not exactly what they want. They want the quick buck for sure.

In this business atmosphere, 2112 (their fifth recording), may have been perceived as a last chance for Rush to succeed. “I never took it that serious. I didn't care. I was young enough that all that mattered was making the music I wanted to make. So I never looked at it as being do or die. So what, what are they going to take away? They can't really do anything. And that's the importance of the whole business side that musicians never face. They never say no because they think ‘Oh God, these people hold the strings to my future and if I don't do as they say...’ I have no patience with that, and at that time in my life I could've cared less. I thought if they want to pull the plug, fine, I got to make four albums. How many musicians get to make four albums? I looked at it only in a positive light: well we got to do all this, who cares? If this is the end, fine, I had a good time. I've always felt that the music I want to play is what I care about. I'm not interested on playing top-40 in the bars, playing the kind of music I don't like. Making my living at it [music] is entirely secondary. What's important to me is making the music that I like. I can make my living any other way, I don't care.”

Peart's attitude is shared by his band mates, Geddy and Alex. Opinions like this have not helped endear them to the critics. But Rush has always believed in what they're doing. Music is a career they happened to choose and succeed at, they could've just as easily been lawyers, teachers, or truck drivers. Just because they haven't been caught up in the rock star mentality and lifestyle doesn't mean they are indifferent. “You get so upset when you see all the insincerity. You see so many bands become successful on a total lie, on an attitude created partly by them and partly by the record company. To see people taken in like that, at least for a while, it makes you very angry. Especially when you're prepared to do it, quote, ‘the honest way’. When you see the sleazes doing it, it's annoying. I get mad about it and I'm inspired to write, because anger is one of the great inspirations that gets me fired up enough to go through all the trouble to put things down.

“There's so much temptation for a band to sell out when a record company says, ‘Look, if you cover this song it will be a hit for you’, or, ‘I know you want to write your own songs, but we've got some good people here that can write hits for you. Just do the song and later you can do what you want’. All those famous clichés, it's ridiculous, because nobody, but nobody ever does that. Because once you've sold out, you lose touch with integrity and have no idea of what you originally wanted to do in the first place. People get so corrupted by the trappings of artificiality. There are a number of rock and jazz casualties who get caught up in something beyond them and totally lose contact with reality, consequently they become lost in alcohol and drugs. It's commonly pointed at rock, but it just occurred to me how much more prevalent it is in jazz.”

Buoyed by the success of 2112, Rush released a live recording that showed the energy and emotion of their live shows. It also signified the end of an era for them. “That was definitely the end of the guitar band days, and the end of an era of searching too, as 2112 marked a point at which we started to find our own ground. The live album thus marked the beginning of being something that was Rush, other than too much of a schizophrenic amalgam. Suddenly, with 2112 we cemented something that I think we were going to be from then on—and then threw it all away!”

The next two albums took the band's epic story telling to its greatest extent. The Cygnus X-I/Hemispheres tale was contained on a side of each album. This dramatic story told of man struggling to reconcile his two halves: the logical and emotional. “The albums can really be lumped together as being one year of university. It's like the first year of studying the technique of music very seriously and doing experimental and exploratory arrangements, really getting lost a lot. In retrospect, I can see that a lot of times we were just flailing and doing things that didn't make any sense. But we learned so much that it's hard to be negative about them. And again, I have to shake my head and smile, because a lot of it was lost, but it added up to something. We were lost in worlds of technique and were leaning more about our instruments as individuals. More about playing together and putting music together too.

“The whole science of arrangement has become, through that period, the focus. At that time the focus was learning and playing the instruments—everything was instrumental. That's what mattered, the little pieces of music. After we went through that, the focus shifted, right up to the present day, the focus is on arrangement—how to put the pieces of music together. That was an important learning process that established something and allowed us to put something to sleep too. Many musicians never get out of the trap of technique being the end of everything. It's still very important, but I'll never be one of the less is more minimalists. I'm never, ever going to say that feel is more important than technique. There's no comparison, unless you know how to express it, it doesn't matter how much you can feel it. That's also an important distinction we had to learn. At the time we didn't know it. Technique was more important than anything else. But that's okay, I think it served its purpose. At a point in anyone's development in a craft or job, you have to go through a period in which the nuts and bolts of the job are absolutely what matters most.”

Technique as an exercise at the expense of the song became the trap of many a fusion or metal band. How many bands have you marveled at for the first half hour, then quickly became bored as it all started to sound alike. “The important thing is to come out the other side. A lot of people never enter that doorway, never go to that school, and they just close that door entirely. I think that's a big mistake. At the same time, many musicians musicians, get into that world, become snobby and small time about it and never come out. They quite literally never get out of school. That in any walk of life is an arrested adolescence and I see a lot of musicians frozen in that.”

These two records also saw the band expanding musically by adding synthesizers and percussion. In many ways, this helped put behind them the heavy metal power trio label that had defined them for so many years. “We added all that and dove deeply into the world of time signatures. We learned how to put two different tempos together, sometimes making them work, but most times not. It's inevitable to explore, and we had some thematic and cinematic pieces that didn't come off all the time. It's not really important that it's successful. The important thing is that you do them.”

As a whole, A FAREWELL TO KINGS/HEMISPHERES has some memorable moments, but often collapses under its own grandiosity, becoming an endurance test for the listener. “I don't look at it as an unqualified success. I remember playing La Villa Strangiato after six or seven years. I had to go back to the album and relearn the instrumental, which is ten minutes long. On the record it's subtitled ‘An exercise in self indulgence’, and it truly was. So I was quite amazed by what we were into at the time. A lot of our songs, if they can be called songs, were truly exercises in learning different areas of composition and arrangement.”

This release found a band that had integrated the synthesizers into shorter, more concise songs. Even Peart's lyrics seemed to be more focused. “We were graduate students, and arrangement became the focus in songs like The Spirit Of Radio and Free Will. Those were our conscious concerns, [but] we still wanted to wail and have our instrumentals on that album. It kind of had a foot in the past and the future too. That's why it's transitional, we were still working in the school mentality and we weren't deadly serious about our new step yet. But our attention was being attracted by the idea of how to put things together, rather than just come up with tricky things and neat little passages. There's a long 6/8 instrumental passage in Free Will, but it was carefully arranged. It was the first time we had taken the trouble to carefully construct the dynamics, work on our parts, and get some sense as to what it was going to be as part of the song.

“In retrospect, I find that album pretty satisfactory. That's probably the earliest album I can still listen to without wincing. Everything before that I have reservations about. There's some nice playing on it and it starts to become more satisfying in a structural and song sense. The album was carefully constructed. Even though it was allowed to breathe inside, it was analyzed in every small sense.”

MOVING PICTURES

MOVING PICTURES

Many musicians spend much of their time searching for that one moment, that special time when all their effort climaxes in a magical event. The music transcends all previous effort and it takes on a life of its own. Still others go about their business and have that magical moment just dropped in their lap, unexpected and uninvited—but welcome still. Such is the case for Rush. In 1981, after steadily building momentum, they released their 9th record, MOVING PICTURES, and watched it shoot beyond all their expectations. The album's opener, Tom Sawyer was quickly adopted by fans as their new anthem. Other tracks, such as Red Barchetta, Limelight and YYZ [pronounced Y-Y-ZED] quickly became favorites.

As Neil explains, “That was one of those magic moments that no one knows why [it happened]. All through the writing and recording it was like any other record, but there was something about it that had built in accessibility. I don't know how we did it, we just did everything right. I wouldn't go back and analyze it. It still is interesting why that album struck a chord and became so popular–I don't know.”

Tom Sawyer, in particular, had a big impact on drummers and would-be drummers. “When you're making it, you're just doing it. You don't make those kind of predictions, just make it the best you can. It's surprising, even a song like YYZ became popular because it was on that album, certainly not because of its commerciality. People were responding so strongly to Tom Sawyer and Limelight, that an instrumental like YYZ could be part of that and remain a popular song where it had no right to be.” Indeed, who could ever predict that a song based on the rhythm of the morse code identification for the Toronto International Airport (YYZ) would become a staple of most bar bands.

Part of the appeal was the overall strong drum sound and presence that permeated the album. Tom Sawyer didn't just start off the album, it jumped out and grabbed you, never letting go. Neil's drums were up front and driving. “Again, that's an accident of the material and the spaces that were allowed [for the drums] by the other instruments. So many little things become a part of saying something like that. You can't say ‘why did the drums sound so good on that album?’ If you strip it down to the drum track and listen to the drums by themselves, they probably sound much the same on any album. But it's what happens when you start putting on guitars or keyboards, how they happen to sound. For instance, on the next album [SIGNALS], the drum sound was much the same, but we were using a different approach with the guitars and keyboards. Consequently, certain frequencies in the drum sound were soaked up and their impact and effect, more than their sound, was totally different.

“MOVING PICTURES allowed more space with that certain sweeping guitar sound and a very minimalist keyboard approach. At that time, the keyboards were still monophonic, so nothing got in the way of the drums. Whenever something did, we would try things like reversing the phase on the bass drums to put them even lower than the bass, if there was a conflict there. It was really easy to squeeze things around. Nowadays, with the more textures that we've introduced into the music, it's more difficult to find room for them all.”

SIGNALS

More textures were certainly on the horizon. With their next release, SIGNALS, they found themselves going full blown into the world of polyphonic synthesizers.

“SIGNALS sent us in to a whole different wave of songwriting. For better or worse, we were trying a lot of different things and changing roles. Sometimes Alex and I were the rhythm section, letting the keyboards take a dominant lead or rhythm role. At the time it was very satisfying, because Alex and I started to think and work that way as musicians. He would have to think about what I was playing rhythmically and play something sympathetic to that. Where as a lead guitar player in the classic mold, he had never done that before. Guitar players are notorious for not hearing anything anyone else plays anyway. So that was good for us as musicians to work that way.

“Songwriting took us in some different directions and we tried to juggle stylistic things. This is the big thing for SIGNALS that obviously other people couldn’t appreciate. For the first time we were taking the elements of English electro-synth music, the influence of Ska and Reggae, and trying to juggle these things all in the same song, making them a part of the same fabric. That made the whole album scizophrenic, jumpy, jerky and sometimes uncomfortable. But the experiments then made songs like Force Ten [from HOLD YOUR FIRE] possible. Exactly the same influences that we tried to weld together on Digital Man, which I look at as pretty much an unsuccessful mix, with the benefit of experience worked on Force Ten.

“It's very smooth and seemless, an effortless transition through very different textural moods and rhythmic approaches. That Is a good example of learning something by way of failure or experimentation that later became the fruit, an actual result of what you tried earlier.”

The most striking of the changes on SIGNALS was Geddy Lee's increasing role as a keyboardist. Moving away from the guitar dominated sound of MOVING PICTURES, SIGNALS is probably the most different of all the Rush albums. As Neil explains, “We had a very thick keyboard sound that we used on Subdivisions and Chemistry. We found places to use all those things later, but, never in a whole song again. It was like a laboratory on wheels. We experimented with these things on the road, and on soundchecks, and they crept into our songs. Sometimes whole songs were built around a single experiment, perhaps not to any good point at the time, but it paid off in the future.”

The most unique experiment was the song Losing It. This gentle song [in 5/4] featured the first full-fledged guest artist on a Rush album. Violinist Ben Mink (then with the Toronto band FM, currently with country star K. D. Lang) added a beautiful solo that set the mood for the entire piece. “Yeah, it remains a very satisfying song to me. I really like that. It has so many elements in it's rhythmic complexity that managed to become very smooth underneath. It's satisfying when you can make that happen. I love the violin solo. I've always loved solo violin when it's really frenetic like that. I find it very passionate.”

GRACE UNDER PRESSURE

As almost an answer to the keyboard heavy production on SIGNALS, the next release, GRACE UNDER PRESSURE went back to a more guitar oriented sound. Neil explains, “We had done a lot of new keyboard explorations on SIGNALS and then a number of changes on GRACE UNDER PRESSURE looking for a more open sound, making the keyboards less of a wash and more of a functional part of the sound. We also had a new producer, so that took us a different way.

“Written in 1983, GRACE UNDER PRESSURE was a reflection of the times when things were very bad around the world. A lot of people interpret that album as being depressing, or a dark look at the world, or some reflection of my inner darkness. In fact, quite the opposite is true. I was very happy and feeling guilty about my own intent and success, because all around me, my friends were out of work, sick, or going through broken relationships and marriages. All these things were happening and I could not help but be moved by them, and what was happening in the newspapers.

“There was a tremendous amount of tension. That was the summer the Russians shot down that Korean airliner. All these things were in the back of my mind while we were making that album. I think that album, and the two previous ones, were stepping closer and closer to reality in terms of the lyric writing. That was the first time I became serious about being topical, writing about the world as it was, not a projection about an ideal or fantasized world for the purpose of using allegory or symbolism, saying here's good and evil. I was done with all that and the Herman Hesse symbolism and just wanted to look at the world and express it in my own way. That album was critical for that, but it was often misinterpreted. My lyrics are still misinterpreted as being about me, when in fact, they are about the people that read them.”

Peart's lyrics have always been a source for debate. Rather than take the easy way out and write boy meets girl songs, he has challenged both himself, and the listener with subjects like ecology, personal growth and freedom, the weight of fame and many others. But like anything, the lyrics are open to interpretation. “That Is where the problem can lay sometimes. If someone is cynical and has a dark view of the world, then they'll take a dark view of what I’m saying. The Perfect example is Middletown Dreams from POWER WINDOWS. I'm talking about people who live in small places and want to get out. And in my mind they do get out and their dreams come true. I leave it a bit vague in the song, but there's always the understanding in my own mind that these people are going to do it. And yet that was often seen as a song about futility, as a terrible condemnation of these little lives, these poor people who would never do anything. My intention and theme was entirely the opposite. I based it on real lives, like painter Paul Gauguin, who was a stock broker until he was an adult, then he suddenly became one of the most influential painters in the world. That's the type of person I used as my theme.

“It's interesting how when you express something, people are free to interpret it, and more often then not, take it just the opposite, according to their own temperament. Certainly GRACE UNDER PRESSURE was an album like that. I perceived it as a statement of compassion and my tremendous sensitivity for the world around me, both the close world of my friends and also the larger world on an international level. Yet so many people see it as a depressing album. I see it as a personal failure, having not conveyed it clearly enough. Now having learned from that, I'm more able to express things that concern or move me without having to make it seem as dark as that.

“I still like GRACE UNDER PRESSURE and find it very life affirming, not depressing. A lot of times as a songwriter you have to say, ‘it's my fault, I didn't convey it clearly’. We've seen it happen with a lot of our songs. Musically and lyrically we love them, have a ball working on them, and we're so proud when they're done, yet it doesn't connect with the people. We've taken the blame even if we didn't know what went wrong. MOVING PICTURES was made in the same spirit as all our albums, yet it somehow connected and went straight to the heart of the audience. Other things we've loved haven't. It's easy to say the audience is stupid and didn't understand. But that's a cop out, because when you get it together and it works, you can connect without having to pander or use cheap gimmicks and excuses.”

Learning, as we have seen, is a big part of Pear tis life. Whether it be from himself, or an outside influence, he has always believed in building upon the lessons learned. “You learn from other people too, like Roger Waters [of Pink Floyd], who's one of my favorite lyricists, although I totally disagree with almost everything he says. His whole outlook on life, his politics and his philosophy are poison to me. But because it's so beautifully expressed, I still enjoy listening to him. I learned a lesson of not wanting to express myself that way, not so cynical and down on the world. There are plenty of writers like that–everything they say I don't like, but I love the way they say it.”

Rush has never been a band to look down on its audience. Instead, they give them enough credit to think for themselves and form their own opinions. “The pandering that goes on in popular music is shocking to me. So many people try to second guess what the audience will like, instead of just making music that they like and hope others will like it too. If you think that you're no better or worse than other people around you, then theoretically a certain number of them should like the same kind of music that you do and you should communicate with them.”

POWER WINDOWS

The next release from the band, POMER WINDOWS, was a major step. Abetter balance between the keyboards and the guitars and drums was achieved. As Neil explains, “It was a major step in arrangement too. Peter Collins was our new co-producer and his focus was on songs and arrangements. That's the main reason we chose him. He doesn't get involved in the technical recording side of things, leaving that to us and the engineer in terms of quality control. He just likes to sit back, close his eyes, and visualize ways a song can be made more effective emotionally. Again, that missing element of reaching the audience. That's his main strength and why it was so important to have a co-producer like him at that particular time. Arrangement became everything to us. The song is important. Writing the music and lyrics and putting it together on our instruments is satisfying, but more than anything, we analyzed the songs saying, ‘can this be better, can we do it in more interesting ways?’ Those are the kind of things that now go on in our musical discussions when we look at a song.

“Manhattan Project was a big struggle. I've always wanted to write something that was a documentary. Lyrically it was a strong goal. I'd tried it in the past and never had been totally happy with the results we even used on record. That song was a real learning experience–trying to write the lyrics and tell the story the way I wanted to tell it, to de-mythologize the ideas about America's involvement in the nuclear age, you know, the common liberal attitude of ‘how dare the U.S. go and blow up Japan, poor innocent Japan’. I wanted to address all these myths and did a lot of research about the subject, learning as much about the people, what they did, and why. At the same time, I was trying to convey it in a rock lyric format. It was a real challenge and Geddy helped me a lot in finding a way to invite people into it. It was his idea to use the lines, ‘Imagine a time, imagine a place, imagine a man’ to invite the listener into the atmosphere and the idea. It was Peter Collins who really contributed to the arrangement, making it richer texturally than we had originally been able to do. It was his idea to use a string section and have the string section do an actual solo. And he pushed us a lot of different ways to get more empathy out of the vocal performances and melodies.”

“Manhattan Project was a big struggle. I've always wanted to write something that was a documentary. Lyrically it was a strong goal. I'd tried it in the past and never had been totally happy with the results we even used on record. That song was a real learning experience–trying to write the lyrics and tell the story the way I wanted to tell it, to de-mythologize the ideas about America's involvement in the nuclear age, you know, the common liberal attitude of ‘how dare the U.S. go and blow up Japan, poor innocent Japan’. I wanted to address all these myths and did a lot of research about the subject, learning as much about the people, what they did, and why. At the same time, I was trying to convey it in a rock lyric format. It was a real challenge and Geddy helped me a lot in finding a way to invite people into it. It was his idea to use the lines, ‘Imagine a time, imagine a place, imagine a man’ to invite the listener into the atmosphere and the idea. It was Peter Collins who really contributed to the arrangement, making it richer texturally than we had originally been able to do. It was his idea to use a string section and have the string section do an actual solo. And he pushed us a lot of different ways to get more empathy out of the vocal performances and melodies.”

As heavy as the subject matter of Manhattan Project was, it was also some of Rush's most beautiful music. “I also like the element of humor that we were able to add to it with the accompanying cartoon. When dealing with a heavy subject, it's important to try to leaven it if possible. The romantic musical underpinning was a conscious effort to leaven it without changing what I was trying to say. Putting it in the best, possible light, the most attractive frame.

“That's something we've learned how to do and have done a lot. If a song has a dark or plaintive atmosphere, sometimes we'll take the exact opposite tone with it. We did that with The Analog Kid on SIGNALS. When the lyrics were written, they sounded as if they should be an acoustic song, or a very slow, relaxed and sensitive song. We decided to take the totally opposite tact and make the verses very aggressive. The musical form on that song later came to fruition on Force Ten. We used very fast, driving verses and then backed off to a very textural half-time chorus. The Weapon [from SIGNALS] is another example. It was a dark topic, dealing with fear and how it is used as a manipulator in the world of religion, politics, and so on. But we set the lyrics to a disco beat. We took a dance music experiment that Geddy had been doing at home with a quarter note bass drum pattern and a very sequenced synth pattern. We took it right out of the framework the words suggested it should be.

“There's no mystery about this album. POWER WINDOWS was very, very crafted, every moment was analyzed and experimented with. We did demo's again and again until we got exactly the right elements. Using Andy Richards on keyboards took us to an area of very high tech keyboard programming and performance. In retrospect, I think we over did his contributions because we were so excited at what he could do for the songs. When I listen to it now, I find it a bit daunting. It's so dense and there's so much information that you are expected to absorb. It must take so long for a listener to get inside it. If I listen with headphones, my ears are so busy trying to pick up all that information. We consciously went into HOLD YOUR FIRE realizing that POWER WINDOWS was more dense than it needed to be. We agreed to record string sections but actually left a lot of them off. And we recorded a lot of stuff with Andy Richards that we just decided we didn't need. We were over the initial excitement and could afford to ask if we really needed it. That was an important process, learning to adjust to a new set of influences.”

Another change on POMER WINDOWS was in Neil’s drumming. While he had always used various percussion instruments, the playing here became more textural. It was a departure from his previous drum style. Neil explains, “Not only was there a change in the electronic sense with Mystic Rhythms, but Territories in the acoustic drum sense. In both of those I was pleased not to use a snare drum with the snares on, and almost never to keep straight time, but to use rhythms as the structure of it rather than the beat. I find more music lately where it Is not based on ‘the rock beat’, but more on rhythm. I see it with Manu Katché on his work with Robbie Robertson, Joni Mitchell, and Peter Gabriel. He doesn't like to play beats, he likes to play around the beat. He does these nice little beats that seem to trace back to Eastern Caribbean music, where it's a hybrid of Calypso and Reggae. There Is that same approach with a quarter note pulse, but there's always that slip-slide snare and tom pattern that makes a rhythm around that. That's also becoming acceptable to audiences in the context of an album like [Paul Simon’s] GRACELAND, that can be so successful based upon rhythmic patterns rather than classic rock beats. I was trying to imagine the Robbie Robertson song, Fallen Angel, without the drum part. Without the pattern that Manu Katché plays so effectively, it Is hard to imagine it as the same song, or at all. It is such an integral part of it, and more so than any drum machine or drummer just keeping time.

“Steve Jansen (of Japan and David Sylvian) was very much an influence on me in songs like Territories and Mystic Rhythms, using rhythmic patterns as the pulse of the song. He was definitely an early influence on me in that area of drumming. I admire him a lot, he's under appreciated.”

HOLD YOUR FIRE

1987 saw Rush again working with co-producer Peter Collins on the HOLD YOUR FIRE album. “Everyone was very conscious of trying to be a little more clean about what really matters. More and more that album represented a trend back towards the three of us: guitar, bass and drums, with occasional keyboards. Force Ten was the last song to be written, and it was easy and very satisfying to write. We were all involved in it, discussing it first before any notes were struck. We talked a lot about what we wanted it to be and literally put it together in the space of one day. Most of the other songs would be 3-5 days of arrangement. As often happens with the last song written on an album, it was indicative of a feeling of where we wanted to go next.

“I think rhythmically in the overall texture of the song, High Water jumps off where Mystic Rhythms and Territories left off. In a way too, it lays them to rest and becomes definitive, closing that door. We still kept a lot of the thick keyboard sounds in Lock And Key and Mission, but we did some interesting things. On Mission I play a drum solo and the other guys accompany me. That was something I always wanted to experiment with more and Peter Collins actually suggested trying something like that. It's great when I have the feeling that suddenly the band is the back-up and I can feel that I'm leading, going off to do my solo for 16 bars, and they keep time for me. That's a refreshing corner to turn.”

A SHOW OF HANDS

The HOLD YOUR FIRE tour resulted in a third live recording, A SHOW OF HANDS. As with the two previous ones, it was a summing up of Rush's music up to that point. It again closed a cycle the three previous studio albums comprised. A highlight of that release was Neil's drum solo, The Rhythm Method. “I gave more thought to the drum solo than definitely any in the past. l thought of it thematically as wanting to present all the different sides of percussion, incorporating roots of tribal percussion and the very darkest sounds of the oldest known drums, but also right up into the modern times of keyboard percussion. Big band jazz and orchestral percussion are worked into it using timpani and orchestra hits. So I had all that thematically, but again, I didn't want to make that the message I was hitting over people's heads, it was just a frame work from which to build. I threw out a lot of stuff that had been in my solo for years, sort of cleaned house and started with a fresh slate of wanting to create a piece of music around which I could show off. I think the function of a drum solo still remains the same: I wanted it to be a thrill for me to play and exciting for the audience. But I wanted some structure and different things that sampling bas allowed me to do, like have a big band backing me up and have symphonic orchestra shots.”

Neil, Alex and Geddy have covered a lot of ground in the nearly twenty years they have worked together. From their first collaboration on FLY BY NIGHT, to their last recording, PRESTO, and their forthcoming release, ROLL THE BONES, Rush has always been true to their fans by being true to themselves. In today's world of manufactured music, they are an inspiration for aspiring musicians everywhere.

***

Whether you liked Neil’s drumming, or RUSH, doesn’t really matter. But every drummer owes him a great debt for making the drums and drummer so visible to the public. And also for inspiring so many people to take up the drums and strive to move drumming forward. He was a quiet man with a big heart, and even bigger drumming. Thanks for the memories Neil!

~ MB

Deconstruct Yourself™

Comments

Post a Comment