Fierce & Uncompromising: Ronald Shannon Jackson

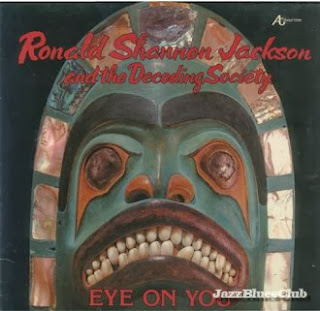

On October 19, 2013, the music community lost one of its most original musicians, drummer/composer/band leader, Ronald Shannon Jackson. I first became aware of Shannon through a magazine interview. He was straight talking, intense, and had a sense of confidence about him like few others. Some would see it as boastful, I saw it as a man who knew both himself and his mission. The focus of the interview was his then new, first solo recording, Eye On You. I ran out and scoured the record stores for a copy. My young drumming self was not prepared for what sprung out of the vinyl groove!

Just like the drummer in the interview, the music was fierce and uncompromising. It hit me the same way that Tony Williams' 'Emergency' had. I didn't really understand what was going on. So I played it a few times, then filed it away. Sometime later, I pulled it out and played it again. I kept doing this until one time it finally clicked with my brain. I finally got it, what Shannon was 'decoding,' and I was hooked.

To say Shannon had a major impact on me would be putting it mildly. I searched for any recording he played on and bought all the subsequent LPs and CDs released. I immersed myself in his music and 'grokked' what he was about. As a fledgling writer, I took a chance and sent him some of the drumming stuff I had been working on. He sent me a very nice letter in reply. Years later, I proposed including him in the book, Percussion Profiles, that I was writing. It took some tenacity to track him down and make a connection. Even then, I wasn't sure things were going to happen, but they did.

Interviewing Shannon was a lesson in patience. When I started, he wasn't talking. Perhaps he'd been misquoted, or just misunderstood in one too many previous interviews. So I kept at it, and finally he seemed to relax and open up, although he was still a bit guarded. When I raised the subject of his band, The Decoding Society, his response was, "Uh-uh, not going there." So the interview became a game of cat and mouse, with me trying to get him to open up on a variety of subjects. This is not to say he was difficult, just guarded. In fact, he was gracious with his time and the things he would talk about.

To say Shannon never got the credit he deserved would be putting it mildly. He was a true pioneer, a visionary even, creating rhythms like no one else. He was also a serious composer, composing string quartets and chamber music. But despite his musical contributions, he never seemed to get the recognition he deserved, especially here in America. I sensed in our conversation that this was a sore spot. Perhaps he was too radical or too larger than life to be accepted and praised by the mainstream. But those who knew, knew the genius he was.

So I present to you, the full interview with Shannon (from around 1999) from my book, Percussion Profiles:

Just like the drummer in the interview, the music was fierce and uncompromising. It hit me the same way that Tony Williams' 'Emergency' had. I didn't really understand what was going on. So I played it a few times, then filed it away. Sometime later, I pulled it out and played it again. I kept doing this until one time it finally clicked with my brain. I finally got it, what Shannon was 'decoding,' and I was hooked.

To say Shannon had a major impact on me would be putting it mildly. I searched for any recording he played on and bought all the subsequent LPs and CDs released. I immersed myself in his music and 'grokked' what he was about. As a fledgling writer, I took a chance and sent him some of the drumming stuff I had been working on. He sent me a very nice letter in reply. Years later, I proposed including him in the book, Percussion Profiles, that I was writing. It took some tenacity to track him down and make a connection. Even then, I wasn't sure things were going to happen, but they did.

Interviewing Shannon was a lesson in patience. When I started, he wasn't talking. Perhaps he'd been misquoted, or just misunderstood in one too many previous interviews. So I kept at it, and finally he seemed to relax and open up, although he was still a bit guarded. When I raised the subject of his band, The Decoding Society, his response was, "Uh-uh, not going there." So the interview became a game of cat and mouse, with me trying to get him to open up on a variety of subjects. This is not to say he was difficult, just guarded. In fact, he was gracious with his time and the things he would talk about.

To say Shannon never got the credit he deserved would be putting it mildly. He was a true pioneer, a visionary even, creating rhythms like no one else. He was also a serious composer, composing string quartets and chamber music. But despite his musical contributions, he never seemed to get the recognition he deserved, especially here in America. I sensed in our conversation that this was a sore spot. Perhaps he was too radical or too larger than life to be accepted and praised by the mainstream. But those who knew, knew the genius he was.

So I present to you, the full interview with Shannon (from around 1999) from my book, Percussion Profiles:

Decoding the Spirit with Shannon Jackson

“l play music. I write music and I play music. That's basically my life. I do what l've gotta do.” So says drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson. In the forty years he has been laying down the beat, he has forged an legacy of some of the most creative rhythms and music in jazz. He is the only drummer to work with Albert Ayler, Cecil Taylor, and Ornette Coleman—the Holy Trinity of free music. His post Coleman Decoding Society, was a ground breaking band that created a true fusion of musical styles he learned growing up in Fort Worth, Texas.

He started playing drums in school, in the third grade, feeling drawn to the instrument. School band gave him the usual background of Sousa marches and classical music, forming a lasting impression on the young Jackson. “My father had jukebox businesses so I could go anywhere. I had a driver’s license when I was 14 because of the business.” Taking care of the jukeboxes exposed him to all styles of music, especially the blues, which would later resurface in his band, The Decoding Society. “l was just playing in bars from the time I was a teenager. Playing professionally making a living by 16, 17. At 18 I left there playing. So l went to college at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. John Hicks, the piano player—he played with Betty Carter and was the musical director for Woody Herman when he died—he and I were room mates in college. Lester Bowie was there, so was Julius Hempill, who I was friends with from growing up in Fort Worth.” Being a part of that crowd was an influence on him and created lasting musical associations. He ended up quitting school and moving back to Texas to take over his ailing father’s jukebox business, but all the while he was gigging. From there he ended up at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut to study business. But the lure of the drums proved too much, and in 1967 he finally settled in New York City. There he got a scholarship to NYU College of Music. But his real education took place gigging around town.

He soon hooked up with a man named Albert Ayler. “Looking back, those were just part of destiny—the word that’s in the environment that would kind of explain that. lt’s not everybody that gets that kind of opportunity. When I went to New York, the second week there Charles Moffet, who was playin’ drums with Ornette—I knew Charles Moffet but I didn’t know Ornette, because they were ahead of me (in school). I knew Charles Moffet because he was teaching in the schools not far from here, and he would be playing with groups around here. He had this record date with Charles Tyler, but he couIdn’t do it. So Moffet asked me to do the record date and I went over to A&R studios, and I was introduced to Charles Tyler. He told me, ‘This song goes like this...(sings) be-bop-so-du-long…’ That was what we laid down and that was the recording. Afterwards, this fellow with a strange beard came up and asked me if I would play in his band. His name was Albert Ayler. I had never heard of him."

Perhaps few people had really heard of Ayler at that time, as his music was so far ahead of the concepts of the day. The opportunity allowed Jackson to open up and play his vision of rhythm. “With Ayler, I played myself. I live and play who I am. This was the first time I ran into a situation where, instead of saying, ‘Modulate here...get soft here...we’re going to do this right here...stay in the background,’ here was somebody saying, ‘Play like you play at home when there’s nobody else there. What you be hearin’ and playin’ then.’ And he actually meant that. Took me more time to get used to it

than it did him. Because I was brought up in the era of being real sensitive, especially to vocals.”

Shannon’s drumming truly opened up and delivered a variety of rhythms. Besides the straight ahead jazz and be-bop, there was funk and New Orleans style cadence, military rolls and beats run through the Southern Gospel of Fort Worth’s churches. This is most evident on Ornette’s ground breaking 1977 release, DANCING IN YOUR HEAD, featuring Ornette, guitarists Bern Nix and Charlie Ellerbee, bassist Rudy MacDaniel (Jamaaladeen Tacuma), and Jackson. This is the first version of his Prime Time band.

The album’s two main tracks are Theme From A Symphony - Variations One and Two. Jackson cuts a rhythmic path across the harmolodics that is part marching band, part funk, and part free form. Shannon’s rhythm is built from the ground up, favoring toms and snare over cymbals. The effect is heavy, propelling things forward with the force of a bulldozer. Recorded at the same time, the recently re-released BODY META opens with Shannon playing a New Orleans Second Line cadence behind the guitars and bass on Voice Poetry. Again he sticks to the toms and snare on all the tracks, giving the drums and the music a fuller sound.

As Jackson has described it, what started out as a short trip to Paris with Ornette, ended up as an extended six month stay where the band rehearsed daily in an old studio. In his free time he absorbed the culture, the museums, the Parisian life. In many ways it was like ‘harmolodic school’ for the band members. He was also given the same freedom to play as himself that Albert Ayler had encouraged. Unfortunately, Shannon only recorded these two albums before leaving Ornette’s band.

From there he went on to work with James Blood Ulmer and Cecil Taylor. With Ulmer, he worked both in his Music Revelation Ensemble, and on his solo album, AMERICA DO YOU REMEMBER THE LOVE?, which featured Ulmer, Jackson, Bill Laswell on bass, and Nicky Skopelitis on guitar. I Belong in the USA uses slide guitar and has an almost funky/New Orleans/Allman Brothers feel to it. Shannon digs into the snare with a driving second line rhythm. His Southern roots run deep. The later recording, ARE YOU GLAD TO BE IN AMERICA?, is a heavier affair often featuring the twin drum attack of Shannon, and Grant Calvin Weston.

He got the gig with Cecil Taylor, who had worked with such drummers as Billy Higgins and Andrew Cyrille, one day when he met Taylor in a club kitchen by telling him he was the best at playing drums, because he played from rhythm instead of time. Taylor called him the next day. Now Andrew CyrilIe's drumming was ground breaking in his moving away from time keeping, to a more floating, free approach to rhythm. But where Cyrille floated, Jackson came crashing in with a full force rhythmic hurricane. On ONE TOO MANY SALTY SWIFT AND NOT GOODBYE, Jackson plays himself. Even while working with a personality as strong as Taylor’s, Shannon was able to stamp his own rhythmic invention on Taylor’s music, creating a lasting impression for those who would follow in his footsteps. This was a meeting of two giant percussive forces. Ever present was the heaviness of his toms and snare. Jackson is one of the few drummers to successfully combine the deepness of the African drumming traditions with the modern American marching cadence.

“My drumming…it’s me. That’s that saving grace and good quality, the fact that I know it’s me. lt’s like when I play my mantra rhythm (two 8th notes, followed by two 16th notes), and I switch it up and do it the other way. l’m not playing anybody or anything other than what l’m hearing, that I’ve been livin’ with, and thinking about it and write it out to the point where that’s what I live and do. And I just think of ways of doin’ that. Like I said, that’s me. My drumming is me. And from the drumming, when you play drums all the time, if you play drums 15 minutes or so, it‘Il raise the hair on your arms up. When l’m down on the snare drum the electricity is there. Rhythmic and melodic ideas occur and you just write em. Write em down. But it comes from sitting down and playing the ideas that are inherent in the rhythmic thing that l’m playing at that time. Rhythm is the whole thing. And obviously I must’ve hit up on the truth because as far as I can see, there’s a very concerted effort to have music in the West work with no drums. [laughs] I was drumming so far back there you don't know they’re there. So to me, that’s what it is, that’s what I live, that’s what I do. So far I put out a body of work that says that, and I hope to put out some more that will even take it to a higher level. What’s out there is certainly not the essence, that is for sure.”

The 80s ushered in Shannon’s own musical vision in the form of his band, the Decoding Society. 1980‘s EYE ON YOU was a bold statement that built upon what he had learned with Ayler, Coleman, and Taylor. The music was a rich, musical gumbo: Jazz, blues, rock, gospel, country, funk, and NawIins second line; all fused together by Shannon's dynamic drumming. Classic 80's recordings, like MANDANCE and BARBEOUE DOG, feature a 2 horn, 2 bass, guitar, and drums line-up. The rhythms are dense, with Jackson often riding on toms instead of cymbals, while the horns and guitar dance on top.

“l have 9 CDs being released (on Knit Classics). Some of it has been released before and some of it hasn't. The things from before were on the Caravan of Dreams label that went out of business. One of the recordings I did there never was released in the first place. I had even forgotten about it. That's the CD titled EARNED DREAMS. Cause it definitely sounded like a dream came back or something.” EARNED DREAMS, recorded in 1984, features a front line of trumpet, sax, violin, and guitar, with the driving rhythms of two bass players and Jackson. The rhythmic gumbo is thick, like on the title track where Shannon lays down an almost country style backbeat on the snare drum with with an ever present four on the bass drum. Bangkok Morning again has that country feel, with Vernon Reid’s banjo and the cowboy style bass line. On top of this, Jackson’s flute and the violin add an oriental melody. Nairobi Cowboy is an apt title, as Jackson plays like a complete African drumming group behind the front line. MONTREAUX JAZZ FESTIVAL features the Barbeque Dog band live in Switzerland in 1983. Adding to the unique sound of the band was guitarist Vernon Reid's banjo. On LoIa, the banjo and fretless bass play in unison adding a slight country tinge to the proceedings.

“Another one that wasn’t ever on CD was called LIVE AT THE CARAVAN WITH TWINS SEVEN SEVEN. That’s on CD now.” Reissued as BEAST IN THE SPIDER BUSH, it features the Decoding Society with guest African drummer/singer Twins Seven Seven and his back up singers. On Ire, Jackson lays it down with Twin’s talking drum and chanting vocal layered on top. The track becomes a community celebration in the African tradition. In 1983, Jackson ended up recording a solo drum album that also featured poetry. PULSE was a percussive assault. “PULSE came back to me when the record company (Celluloid) shut down. We were actually making BARBEQUE DOG at the time I recorded it. I enjoyed it. I had a nice time. The long drum piece on that particular recording, I like to play. And if I’m going to record, I like to play over a period of forty-five minutes to an hour. Then take a nice long break, and them come in and record. We were in London doing that, and I went in early and started playing the last day of recording. (Producer) David Breskin and (engineer) Ron Saint-Germain came in, turned on the equipment and recorded it. Then when I stopped playing, (guitarist) Vernon (Reid) stuck his head out the door and said, ‘Why don‘t you play that thing.’ He’d seen me do it when they‘d come to rehearsal. I used to do this thing, (Shakespeare’s) Richard Ill and Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven. So someone heard these tapes and that‘s the first time I worked with Bill Laswell on a project. He came to me and asked if I’d complete another 20 minutes to put it out as a record. So then I went back in the studio. David Breskin had given me a copy of Sterling A. Brown’s poems. Since I was really a socially ignorant man, I just read his book until some of the things struck me in that way. And I just recited them as that. I’m glad it’s coming out. It’s now called PUTTIN’ ON DOG. My daughter’s on the cover. Next year will be her last year at Julliard. She’s majoring in modern ballet there."

PUTTIN’ ON DOG is Shannon's most personal statement. Puttin’ On Dog has him playing a Ioping bass drum rhythm behind his voice. The drumming can be as incendiary as on Hottentot Woman, or as gentle as Last Affair: Bessie’s Blues Song, recited by Michael S. Harper. Slim In Atlanta is two and a half minutes of the most amazing groove as only Shannon can play. But nowhere do the rhythms run as

on Richard III, Raven. When he recites "now in the winter of our discontent,” the drums come crashing in with full force, emphasizing the discontent of today’s society.

“A lot of these things Rob McCabe was able to enhance and make sound much fuller, more like today’s material. I think some of the artwork came out very, very good, as opposed to somebody just throwing something on there. Knit Classics pursued this, but it's mutual. I played at the Knitting Factory last June and I think this is the result of it. I think it's good. I know the music’s good and it’s there for other people. Now they’II be able to hear it. This music was never really distributed in this country. Man, I have two records recorded in Europe that never came out over here. One of the things was recorded in Warsaw (Poland) with the quartet that did the CD called WHAT SPIRITS SAY. At least people will have something different. lt’s coming from the viewpoint and perspective of the drums. Coltrane played the saxophone, Mingus played bass, Charlie Parker and Ornette played alto, and Albert, Trane and other people played tenor, Thelonius Monk played piano. This music is coming from the visions of a person who played drums."

You can’t talk about Shannon’s music without mentioning Last Exit. Like a meteor, they blazed a trail across the musical sky in the few short years they existed. Featuring German iconoclast Peter Brotzmann on sax, the late Sonny Sharrock on guitar, producer Bill Laswell on bass, and to anchor the whole full frontal assault, Ronald Shannon Jackson on drums, they were loud, brash, and in your face. Always a step out of time with the mainstream, they played a brand of music more akin to speed metal than the jazz they all came from. Even given the eclectic nature of their musical backgrounds, Last Exit was a brutal assault upon the listening public. Hated as much as admired, they exhibited a no frills approach to music: show up, play like hell, leave. Of their 6 or so recordings (it's difficult to tell, because things have been repackaged and re-released on so many small labels), only one, Iron Path (Virgin), is a "legitimate" release. The others are all pieced together from cassette board tapes, adding to the underground feel of the proceedings.

Shannon's role was as much instigator as that of rhythm player. His modern tribal drumming brought a sense of deepness with it, as if he had been playing these rhythms for hundreds of years. Like a medicine man, he stirred up a wicked brew and cast a spell on all who ventured to listen. They played a few "songs," old blues standards that were used as a vehicle to launch the band off into unknown territory. Ma Rainy and Big Boss Man featured vocals tossed out by Jackson. But the territory they reveled in was fierce, uncompromising improvisation. The self titled, LAST EXIT, is as uncompromising as it gets. The opening track, Discharge, has Jackson playing a whirlwind across his snare and toms, while Laswell anchors things with his 6-string bass. Sharrock and Brotzmann both wail across the rhythm section. This is not music for the faint-of-heart. Catch As Catch Can opens with Laswell‘s distorted bass and Jackson laying down a heavy rock beat. But as Shannon often does, he eschews the ride cymbal in favor of his toms, creating a heavy, tribal feel.

The studio recording, IRON PATH, cleans up the live cassette sound, but only slightly, as the music is still distorted and overdriven. The opening Prayer starts out with bells and atmospherics, as if calling the faithful, only to burst into a speed metal workout that would give bands like Metallica and Slayer a few lessons on being heavy. In the liner notes, Jackson says, “Last Exit is the second coming of the Ayler principle. I am totally at liberty and have total freedom to create and evolve things.” And evolve he does, always pushing his band mates, always working to connect with the spirit of things.

The appropriately named, HEADFIRST INTO THE FLAMES, is a good example of a band living on the edge. Jackson digs deep and pulls out rhythms heavy enough to send any rock drummer who thinks he has it all down, back to the woodshed. No One Knows Anything starts out with a sax/schalmei duo between Brotzmann and Jackson. This is as calm as things get. When he moves back to the drums, the voodoo rhythms heat things up to the boiling point again.

Even with such a long and distinguished musical career, Jackson finds it difficult today to find the right channels to release his music. The funding for jazz keeps drying up. “l've created a large body of work, but trying to get paid for it. I'm always writing. I'm writing some string quartets now. To me it's a responsibility. l've been given the good fortune to hear and do it. The real challenge is to get it out into the environment. lt's a job, beyond a job. Because, what's created is basically not wanted. I just write and work on the music. If there's some good people out there who know that to fight ignorance and selfishness, that other things have to be put out there, [or] the environment gets to the point where people are only allowed to hear certain music. So anyway, I write and I play music. Sometimes the opportunities appear, you just hope that does. Leaders are not really encouraged these days.”

Besides drums and flute, Jackson plays the shalmei, a middle-eastern double reed horn, often with multiple bells. “I have these different horns here, and it makes me hear and write different, especially playing all rhythmic things. I hope these things work out. And I hope to hear from other people who are interested in the way I play. The way that I perceive and hear and play music. At the moment, I'm working with a bass schalmei. It consumes a lot of energy, but it only has four bells. Anytime I play something it puts me in a different tone space, as opposed to playing soprano. I begin to hear differently. lt's how I keep writing something different, because I'm playing something different. The fingering is different. Between the physical and mental focus on the manipulation, there's also how to not force, but very lightly shout notes out of a horn. And it takes time—hearing it and feeling it, learning how you can use it. There are sounds I know that haven't been projected into the environment, but I have to synthesize it myself to the point where when I do project, it's like the rhythm mantra I started on the SXL CD done in Japan in the late 80s. lt's something I started working on with Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. When a lot of players, when they think of playing be-bop, they're playing, ching- ching-a-ching. When they're playing rock or pop, they're usually putting the back-beat on. The ideal worked on, until I could get it to be a part of my everyday living, is two 8th notes followed by two 16ths. Here again, not just using that statement as it can be written, but how can it be pushed out. Not in a hard way, but in a way that works if you're playing a ballad, playing fast. I hear it all the time now and just keep working on that.”

"Yes, of course I have a style. In reference to the term that‘s most used is idée fixe. lt‘s definite that you hear the sound of Louis Armstrong, Horace Silver, Miles, Coltrane, Mingus, Colman, Ayler, Taylor—because it is a distinct idea. The problem is, I happened to be the person who thought about it and synthesized it as a way of life. I still live it. So you get punished for that. You may have come up with it, but you'II sure have a hard time finding where the money went. And if you do find it, it‘II get tied up in some other liquid channels. [laughs] Forget about getting any credit for it—no, no, no. lt's so ironic, because the people who are doing it, are the people who cherish credit for doing what they do more than anything. I just try to live my life. I was doing this and l've always played music. That’s just one focus of it. lt’s like a tree that keeps growing. When you do it everyday, the more aspects you are into, because it's something you do. lt‘s not like a practice or exercise. Everyday you do it, and everyday is different.”

Jackson has been practicing Buddhism for many years, and there seems to be a distinct spiritual side to his music. “Always. What you don't get from a lot of people being put in front of you, is just that—it's an absence of spirit. And spirit is not something we as humans, as far as the music is concerned, choose. We choose to block it. But it's not something that can be bought or demanded. It's something that's either there or not there. lt’s also a way of life. None of the people I named, including myself, decided we were going to play music. lt's something that was there. I became conscious of it at 4 years old. I had one of those very clear, conscious moments in the early years of my life. Then by the time I was 7, I was playing piano recitals. So it's not something I decided later in life.

“I grew up in a situation where my father had a jukebox business and record stores. Then in school they had band from the third grade on. Now days, they've taken all the music out of schools. Which is one of the problems with what’s goin on now. They closed up all the places for people to get together and play. I was back in New York in April. Man, if you go to some of those places you actually need a corporate credit card, so you can write it off as expenses. lt's very expensive. As a musician, l‘m given the privilege of not having to pay the cover, but if you get a cognac and a beer later, forget it. Forty dollars? They’re really going for people to come out to dinner, starting at eight. When I first got to New York, the first show didn’t start ‘til ten, and we didn’t get through playing ‘til four. Now you go to New York and everything’s over by one o’clock. The only thing open down in Times Square is McDonalds to eat at.

“There‘s no place for people to learn how to play. Like playin’ with singers and a whole variety of different instruments. Playin’ a gig with just a saxophonist, playin with trios, with quartets, big bands; all these things are gone. lt’s almost narrowed down to a school type of thing, which is what I think has caused the problems with classical music, puttin’ it in the schools. In three fourths of the world people play some of the most beautiful music, it’s just not being heard over here. lt’s like the tree that fell in

the forest. Like traditional music from Mauritania. You go down in the Aleutians in Spain, and the Gypsy guitar players, man, they’ll have you cryin’. Go down to West Africa—all over Africa—people play music every night as a part of life. lt’s just like eatin’ dinner. lt’s a part of life. Here you’re supposed to go to school for four years and learn what everybody else knows already? And they don't seem to have a problem of startin’ on time, of improvising, bringing it out, or all stopping together. How come three

fourths of the world knew that? Here you’re supposed to go to school, but by the time you’re out of school, you’re really in trouble.”

“lt’s like when I grew up here, I played music in the high school, but the band director at the school went around and chose the people from the different elementary schools who were gonna be in his band when they went to high school. And the people who were chosen to play in the elementary band were chosen by the community too. It wasn’t something where you jump up and say, ‘l’m gonna do so on and so on…’ But this thing is not just music. You go down to Soho—I go down and look at the galleries and say, ‘Wait a minute.’ The Vasquez and Warhol stuff is just disappearing like zooop. You

try to find something, but there’s no real thinking going on. And that requires people who are doing what they’re doing to a point where they let other things in at the same time. And when people ask me, I’ve been to a lot of countries and always said that you should take the music that’s here and enhance it with different ideas. I mean, this country has a problem with art.

“I play music and I play rhythms. I play them and I work on it because I hear something, then I just go sit down and start working on it. It’s like when my wife first asked, I’d be writing music all the time, she’d say ‘What are you going to be doin’ with all that music?’ ‘l don’t know…’ I just know that I be hearin’ it and if I keep writin’ it, it’s going to come. It’s like a dream, if you don’t write it then, you won’t write it. You just keep doing that man, you know? I read a lot. I read a lot of magazines. People just send books and stuff. I’m very fortunate in that sense. There are people out there who obviously respect and enjoy what I’m doin’. This way I get very interesting books that have already been screened. [laughs] I’ve always liked to read, like having a conversion with somebody, especially if they do that as a craft. It’s become a lamentable situation where there now is a lack of places for young musicians to play and learn their art. That’s how most of the music develops. It’s the business part when you have to take it out into the arena, the big arena where nobody can hear it except those standing around the monitors, but they can’t hear it cause the monitors are too loud. Music is about business. Unfortunately it’s not about what it’s really about, and it’s something that we as humans have all over. It’s not one section, or one group, or one tribe of people that have it. It’s all over.

“I auditioned a whole lot of guitar players. They could read, but when they got through playin’ what was written, they look at you sayin’, ‘Alright, what do I do now?’ It’s like they’ve been stamped on. It’s like mediocrity is here today. I mean, corporations need people that are totally reliable, and big companies are started off by creative people, but after they get it runnin’, it’s just a functionary thing. Creative people have to be creative. So you have this situation where you really don’t have anything. The next thing that’s goin’ to be big is this techno thing. But the people don’t have anything to do with that! They never stopped and thought about the fact that they don’t have anything to do with it. l think it’s computerized. It is. Music to me though, I’d rather hear the spirit of a person. One can be tranquilized, like a lot of electronic music will do it, trance and tranquilize. Or one can be...inspired. You know, people can hear things that come from the spirit inside and do something also. It’s just how I can get an opportunity to carry this music to the fullest capacity that I can? Some of it’s played in classical music, smaller scenes, chamber music, but it’s a possibility of getting those things done.” We should all hope that the right situations present themselves, so that Shannon’s music can reach a wider audience. The message still needs to be decoded.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment